Previous Viral SMS-Based Disinformation Campaigns Warn Against Mistaking Online Pranksters for Foreign Russian Trolls - and Vice Versa.

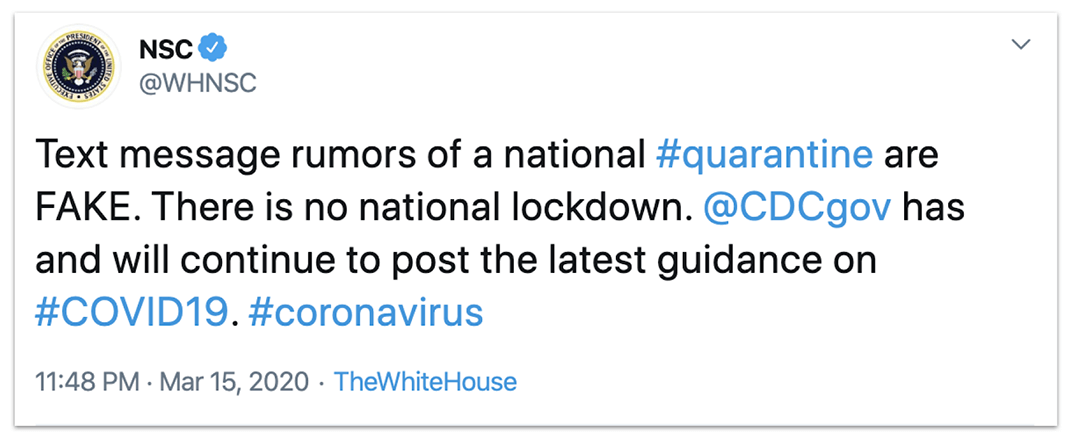

As a viral SMS spread from one phone to another in the US, the National Security Council turned to Twitter{: target="_blank"}, using its verified account and posting from the White House, to correct the record:

Following the announcement, and throughout the viral spread of the SMS, some observers questioned whether the SMS could have been part of a foreign information operation. The Associated Press reported that administration officials were investigating{: target="_blank"} this hypothesis. At Graphika, we received many similar questions.

Scholars{: target="_blank"} have made the case for why the covid-19 pandemic provides foreign adversaries in general, and Russian disinformation operators in particular, with an opportunity to continue sowing discord by leveraging information operations. In the past, Russian information operations focused on creating panic in the US have indeed used SMS, most notably the Russian Internet Research Agency in the 2014 “Columbian Chemicals{: target="_blank"}” hoax.

This is not to say that any viral and false SMS targeting a crisis situation serves as an indicator of a foreign information operation. This short blog post reminds readers that there are often alternate hypotheses at play, for instance US-based pranksters who encourage one another to craft and spread false SMS for “fun.” We here share a prior case study, where we investigated the source of viral SMS designed to make users think they would be drafted into a war with Iran.

The purpose of this post is to urge internet users to caution. The coronavirus crisis is a time of greatly heightened fear and tension - the perfect breeding ground for inaccurate information to spread. That includes fears about both the virus and about foreign information operations that may seek to weaponize them.

The Mysterious Messages

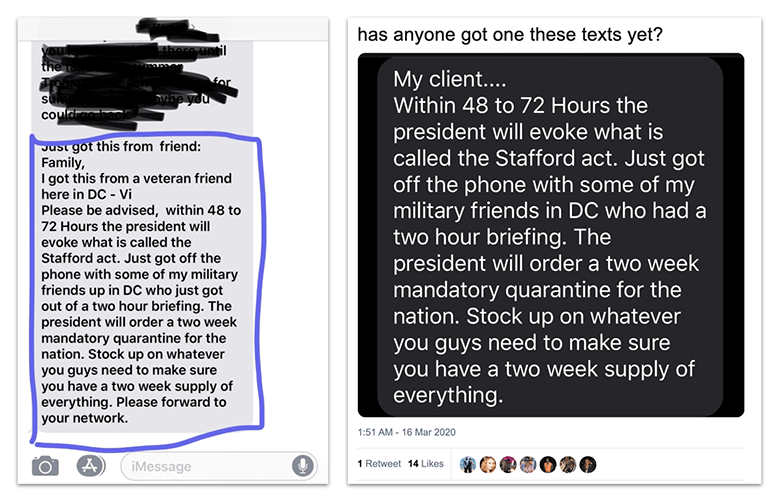

On March 15, screenshots of SMS text messages began circulating on social media platforms. The messages varied in their alleged sourcing, but most shared the same essential wording:

Please be advised, within 48 to 72 Hours the president will evoke [sic] what is called the Stafford act. Just got off the phone with some of my military friends up in DC who just got out of a two hour briefing. The president will order a two week mandatory quarantine for the nation. Stock up on whatever you guys need to make sure you have a two week supply of everything. Please forward to your network.

Different versions of the message were attributed to a “mentee in D.C.{: target="_blank"},” “a friend in the military{: target="_blank"},” and a “veteran friend here in D.C.{: target="_blank"}” Other attributions reported later by the media included “my client{: target="_blank"},” a “friend of a friend who works for Cleveland clinic{: target="_blank"},” and “Andrea’s coworker{: target="_blank"},” while tweets without the screenshots on March 16 attributed it to a “source in the DoD{: target="_blank"},” “someone at the Dep of Def{: target="_blank"},” and a “couple of family members of mine who work for the government{: target="_blank"}.” The messages spread across platforms - notably Twitter, but also Instagram, Facebook, and 4chan¹.

Screenshots of the text messages. Left, from4chan{: target="_blank"}; right, fromTwitter{: target="_blank"}, viaVox{: target="_blank"}.

The “Stafford act” texts were clearly based on a shared original, with the source modified by the sender; the exact wording match, the mistaken use of “evoke” instead of “invoke,” and the capitalization of “48 to 72 Hours” all confirm that this was one message being copied and pasted around, rather than a multitude of messages independently created by different senders. Online, it fed a frenzy of related posts and articles wondering about the veracity of the “Stafford act” rumor, pushing fact-checking{: target="_blank"} organizations{: target="_blank"} and media{: target="_blank"} outlets{: target="_blank"} to address the concerns.

Pranksters and Trolls, United by the Lulz

Many were quick to wonder if these could be linked to a foreign information operation. There are indeed precedents for foreign information operations using text messages to spread a crisis hoax. On September 11, 2014, for instance, the Russian Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg sent text messages to residents of St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, claiming that a nearby chemical plant had exploded{: target="_blank"}. The operation spread the same story across Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, CNN’s iReport community forum, and even Wikipedia. It was, at the time, quickly dismissed as a hoax. That is understandable, as little was known regarding Russian information operations targeting US audiences on social media around September 2014.

Ironically, in 2020, there appears to be a greater danger of audiences assuming that hoaxes are information operations than the reverse.

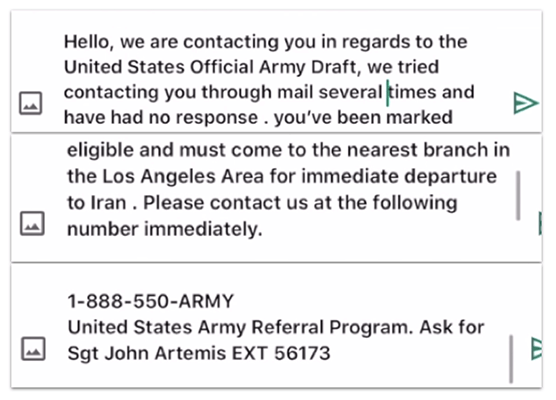

In January 2020, after the United States killed Iranian General Qasem Soleimani, a spate of text messages warned Americans that they had been drafted for the expected World War Three. On that occasion, the Army Recruitment Office published{: target="_blank"} a rebuttal, triggering speculation{: target="_blank"} that the messages had been sent by an Iranian influence operation.

Graphika investigated that incident at the time and concluded with high confidence that the messages were, in fact, the result of a viral prank triggered by a YouTube influencer. Using free online services to generate fake phone numbers, at least 30 different American pranksters inspired by the original influencer sent spoof “draft” messages to their friends, recorded their reactions, and posted the results on YouTube.

There is no indication that these spoof messages were intended as anything other than a joke, nor have we yet found any indication that foreign actors were involved. This case highlighted how accessible and widespread the tools and methods to perpetrate such hoaxes were.

The “you’ve been drafted” hoax began with a YouTube influencer whose primary content is pranks of various types. On this occasion, the prankster used an unnamed online messaging app to generate a new mobile phone number and then used this number to text various friends with the message that they had been drafted.

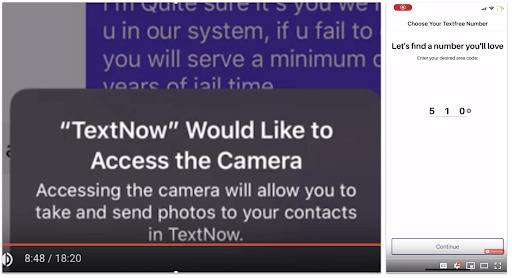

Screenshots from the YouTube video, showing the original prank text.

The prankster typically informed each victim within a few minutes that it was a prank; however, the end of the video included a call to “do this on your friends and family and get their reaction, ‘cause some of my friends’ reaction was hilarious.”

In the following days, at least 30 other online pranksters copied the trick. Some of them named, or showed screenshots of, the apps they used to generate their cover phone numbers; these included TextNow{: target="_blank"}, TextMe{: target="_blank"}, and TextFree{: target="_blank"}.

Screenshots from two separate YouTube prank videos, showing the “TextNow” app (left) and the “TextFree” app (right).

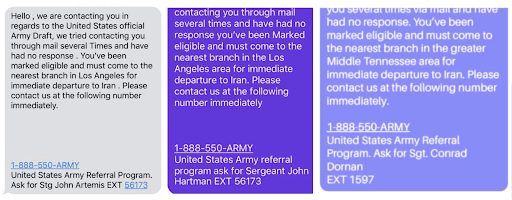

These follow-up pranksters used the same basic text as the originator and credited the originator for the idea, but they changed some of the details, notably the name of the alleged recruiting officer, the extension number, and, in particular, the location of the recruiting center.

Screenshots from three prank videos, showing the same essential text with variations. 1 and 2 give a Los Angeles location and the same extension number but a different name, while 3 references the greater Middle Tennessee area and gives a different name and number.

This was a prank, not an information operation; one of the pranksters underlined, “this is not a joke to the Army people, it’s a joke to my friends.” Another, who faked his own call-up to prank his girlfriend, said, “I’m not going to get too crazy into politics on this channel, nor do I want to.”

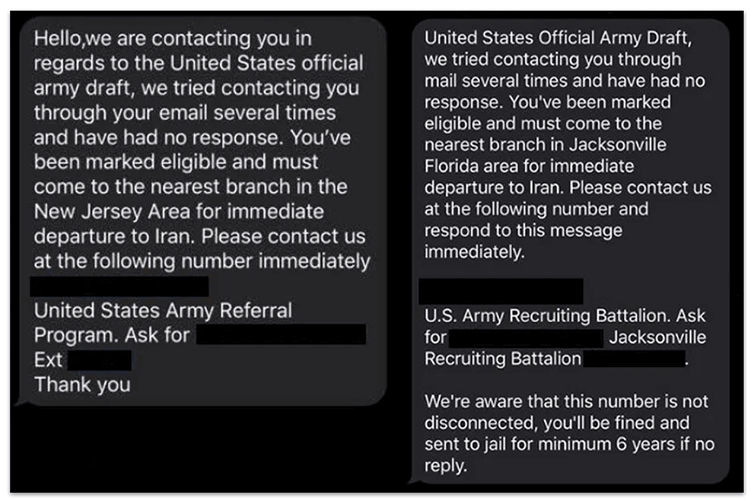

However, on January 7, the Army Recruiting Service took them seriously enough to publish a formal rebuttal{: target="_blank"} that included screenshots of the offending messages. These used almost the same text as the YouTube pranksters.

The Army Recruiting Service rebuttal; note the slight variation in text from the examples given above.

The You’ve Been Drafted case study shows how easily online pranksters can access fake phone numbers and create a viral false message and how easily those pranks can spill out of control and warrant response from the authorities.

The search for the origin of the Stafford act story revealed a long trail of similar claims, posted on social media rather than by text message, that appeared to have been created by everyday users rather than an online operation. This suggests that, at the very least, the chance that the text messages were also an American hoax should be carefully considered.

Early Coronavirus Hoaxes

As with any crisis, humor is an important component of anxiety management and a natural collective response. This has, of course, yielded a series of ealy COVID-19 related pranks online. A few of them have already made headlines, and Buzzfeed’s Jane Lytvynenko has maintained a tracker{: target="_blank"} of instances of coronavirus hoaxes.

On January 30, NBC San Diego reported{: target="_blank"} three different versions of a false claim circulating on Snapchat that students at local schools had tested positive for the virus. Two appeared to have been created on a pranking website; the third was a photoshopped version of a genuine news article.

On February 10, one YouTuber with 19 subscribers posted a prank coronavirus call to a local food outlet, claiming to represent the State of Texas health department; on February 29, another called a local 7/11 store claiming to be an employee who had tested positive for the disease. By early March, various{: target="_blank"} compilations{: target="_blank"} of “coronavirus pranks” had been posted on YouTube; these largely featured pranksters pretending to be carrying the virus in public, rather than making prank calls or sending prank messages.

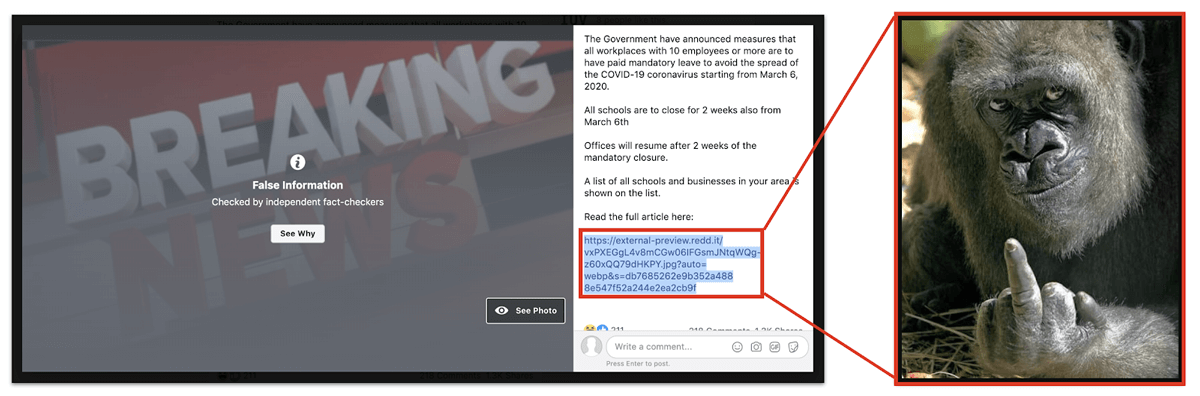

Specific claims of a nationwide lockdown have been circulating at least since the beginning of March. On March 4, a number of Facebook posts spread the claim that the government had “announced measures that all workplaces with 10 employees or more are to have paid mandatory leave to avoid the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus starting from March 6, 2020.” The posts included a link to Reddit; this in fact led to an image of a gorilla showing its middle finger. Facebook marked these posts as false after they were checked by factcheck.org{: target="_blank"}.

Left, one of the Facebook posts that made the claim; note the fact-check block over the image. Right, the image that the Reddit link led to.

Several{: target="_blank"} different{: target="_blank"} accounts posted the identical text on March 4-5; others added a level of local detail in very much the same way that the “Iran draft” pranksters had done, specifying locations in Florida{: target="_blank"}, Indiana{: target="_blank"}, and Michigan{: target="_blank"}. This suggests that various copycat pranksters had picked up on the original idea and decided to replicate it, but in a way that was appropriate (or inappropriate, depending on your point of view) to their local area. None of the accounts showed any indication of being a political influence account: their posts were a mixture of personal and comic content.

Claims of shutdowns on the local and national levels continued to spread. On March 10, NBC San Diego reported{: target="_blank"} that another prank website had posted another false claim of a coronavirus case at a local school. The same day, a school in Arizona{: target="_blank"} posted a report of a phone hoax perpetrated on a pupil by a family member:

A family at one of our schools was a victim of this just recently: a relative in California had their neighbor call one of our parents saying they were a representative of the Centers for Disease Control and that her daughter was exposed to coronavirus, and had to be quarantined for two weeks.

None of that was true.

On March 12, Twitter{: target="_blank"} users began reporting a voicemail message that warned of an upcoming “four-week quarantine” that would include a ban on food shopping. The message{: target="_blank"} cited “my cousin that works for the Pentagon, my aunt that lives in D.C. and my friend that works for the government” and advised the recipient to “stock up on canned goods, frozen food, things that you’ll be able to survive off of for two weeks or four weeks.” Simultaneously, other Twitter users began spreading the same message. Fact-checker Jason Puckett collected{: target="_blank"} some of their posts. Three days later, the fake text messages began circulating.

¹ 4chan is a frequent source of disinformation, but in this case, the images were shared from other platforms, and the tone was questioning rather than gloating.