Fake Accounts Quote Bram Stoker and Boost Pro-China Spam Network

A network of inauthentic Twitter accounts that exhibits strong signs of automated behavior has been amplifying the pro-China political spam network that Graphika has nicknamed “Spamouflage.” The accounts appear to be the work of a single entity, and all post apparently automated quotes from Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”; as such, we call this “Dracula’s Botnet.”

The network appears primarily commercial, as it retweets a range of content in several languages; it is most likely a network of automated accounts for hire. Its accounts are unsophisticated in their behavior and camouflage. Many have been taken down, and few of those that remain have any followers, so the amplification is unlikely to have reached authentic users, but they highlight the way in which fake accounts, spam and influence operations overlap and reinforce one another.

Despite the lack of discernible impact, Dracula’s Botnet is an important reminder of how interconnected different forms of inauthentic inactivity can be. Fake accounts such as these are the plankton in the disinformation sea: they appear insignificant individually, but they can feed larger, more sophisticated operations. They can also reveal them, if a set of inauthentic accounts providing commercial amplification suddenly turns to geopolitical themes.

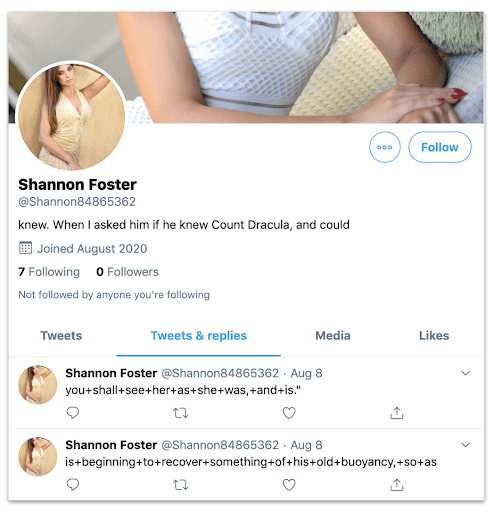

Dracula’s Bot: the account @Shannon84865362, showing an incomplete reference to Dracula in its bio, and two quotes from the novel as its only tweets, with the words separated by + signs.

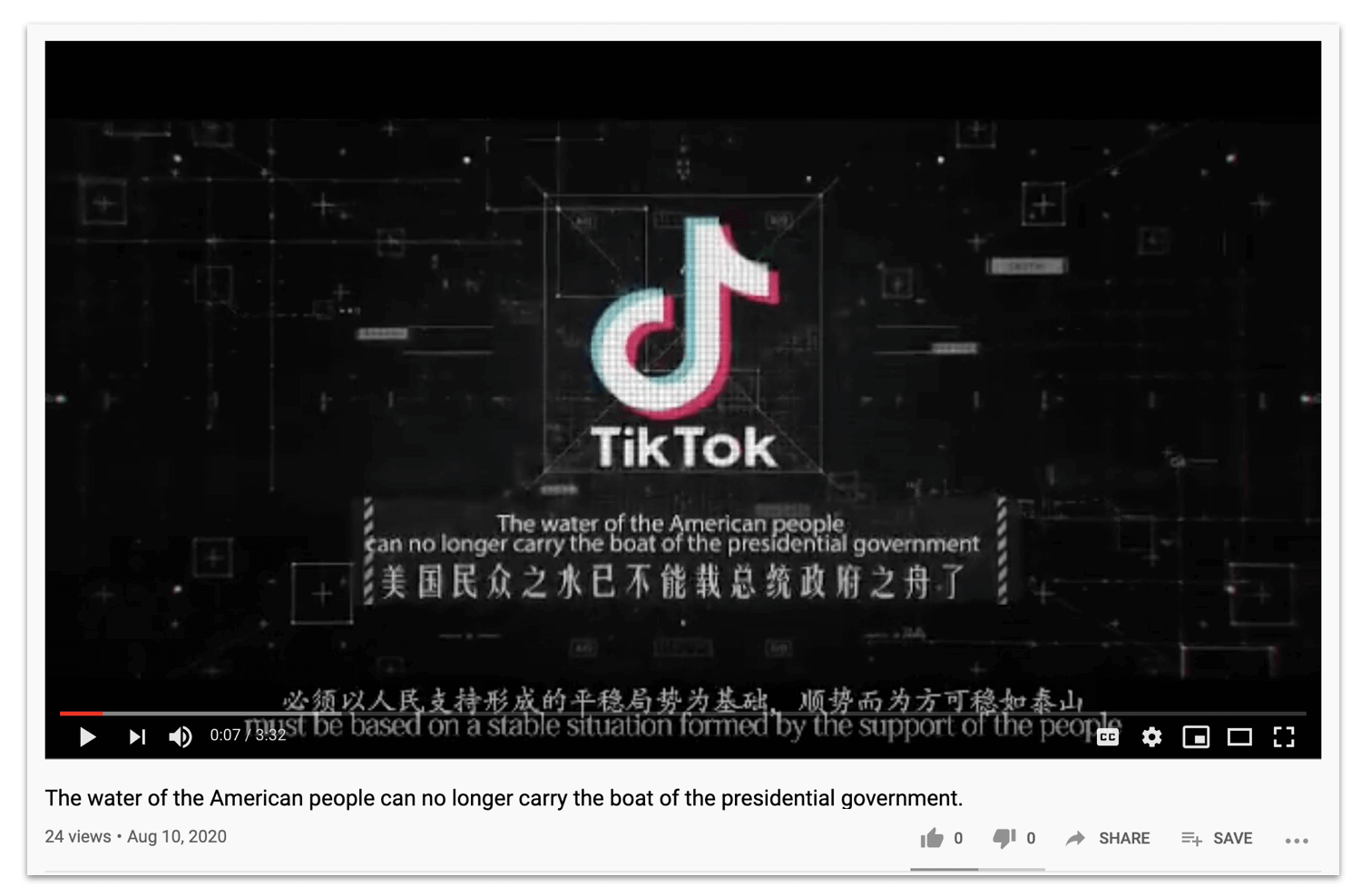

Spamouflage is a large, cross-platform, political-spam network that Graphika first exposed in September 2019. In its initial stages, it posted in Chinese and focused on the Hong Kong protests and exiled Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui. In early 2020, it started posting about coronavirus, still in Chinese; in June, it added in English-language messaging about U.S. politics, U.S.-China relations, and TikTok. Some of its English-language headlines were memorable.

“The water of the American people can no longer carry the boat of the presidential government.” Spamoufage video headline, August 10. The YouTube account that launched it has since been terminated.

“The water of the American people can no longer carry the boat of the presidential government.” Spamoufage video headline, August 10. The YouTube account that launched it has since been terminated.

Especially in English, Spamouflage was centered on YouTube, but it used accounts on Facebook and Twitter for amplification.

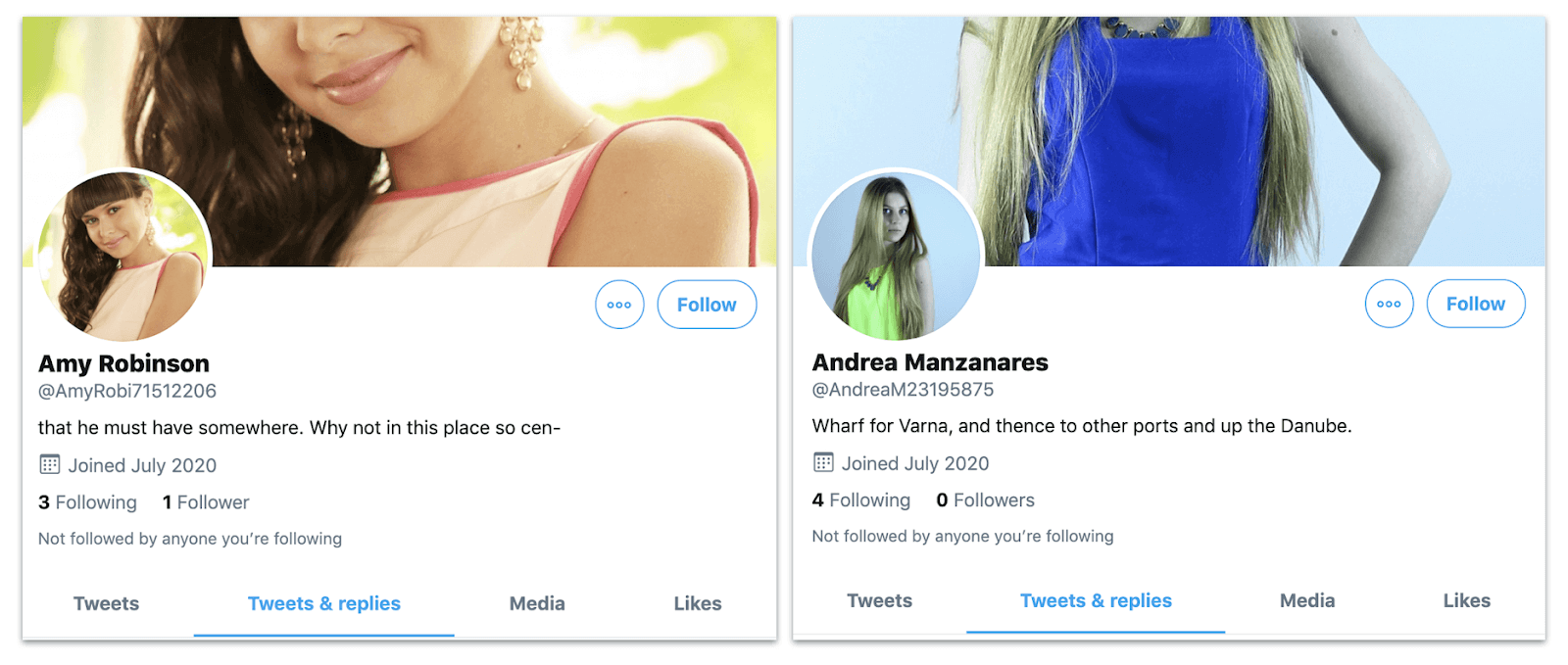

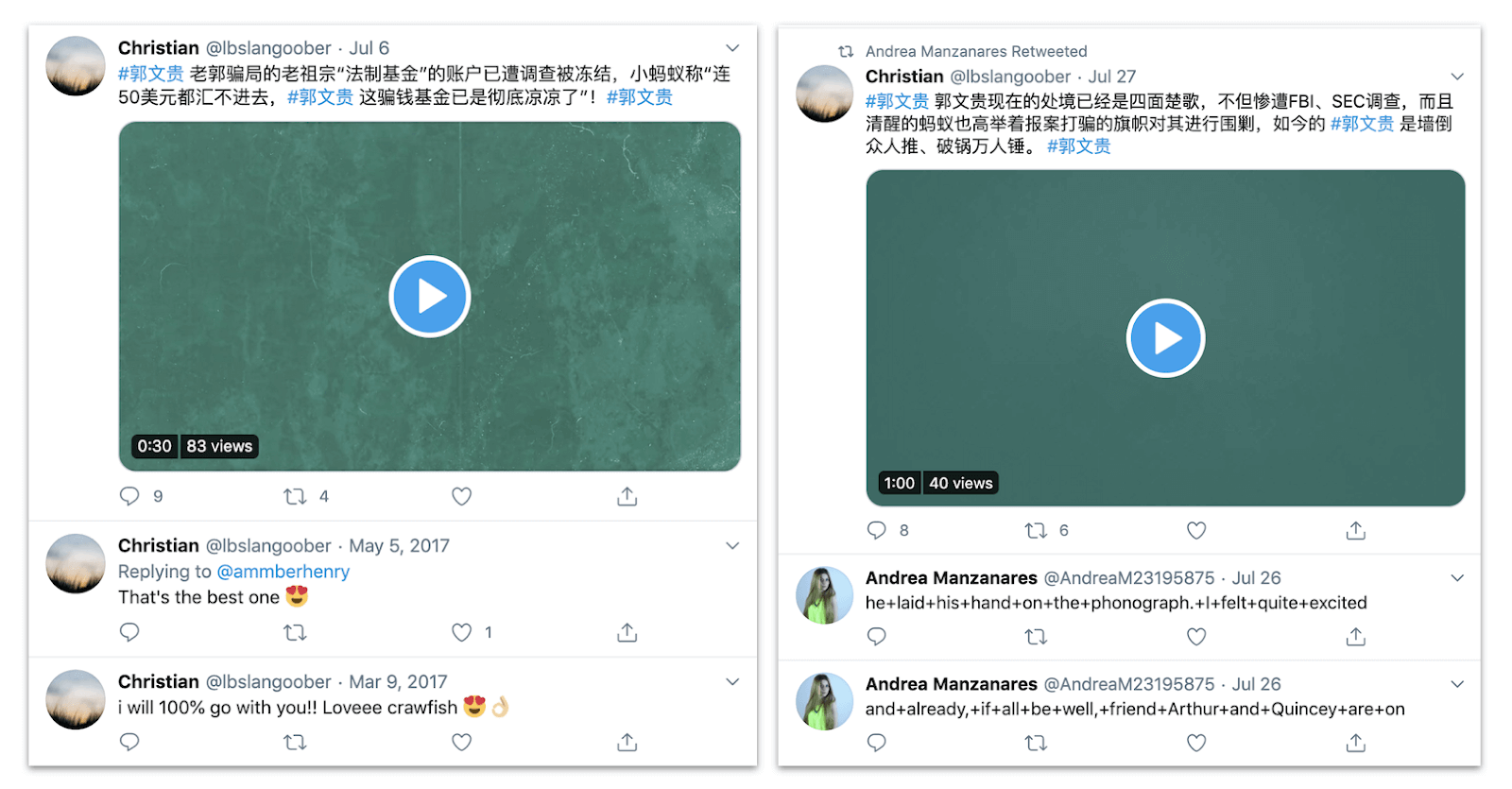

Retweets by the accounts “Andrea Manzanares” and “Amy Robinson” of a tweet by Spamouflage account “Michael Ridenhour,” an apparently compromised account (all accounts were suspended soon after these screenshots were taken). The tweet, in turn, led to YouTube, in typical Spamouflage style.

Retweets by the accounts “Andrea Manzanares” and “Amy Robinson” of a tweet by Spamouflage account “Michael Ridenhour,” an apparently compromised account (all accounts were suspended soon after these screenshots were taken). The tweet, in turn, led to YouTube, in typical Spamouflage style.

Among the Twitter amplifiers were many that showed strong features of commonality. They were created in the summer of 2020, and had few or no followers. Their handles consisted of seven letters (typically abbreviations of English first and surnames) followed by eight numbers. Their profile pictures were stock shots of female models, often with the face partly or wholly obscured, and those which had bios took them from “Dracula” - not in the form of full quotes, but as fractured sentences, most likely generated by scraping an e-text of the novel.

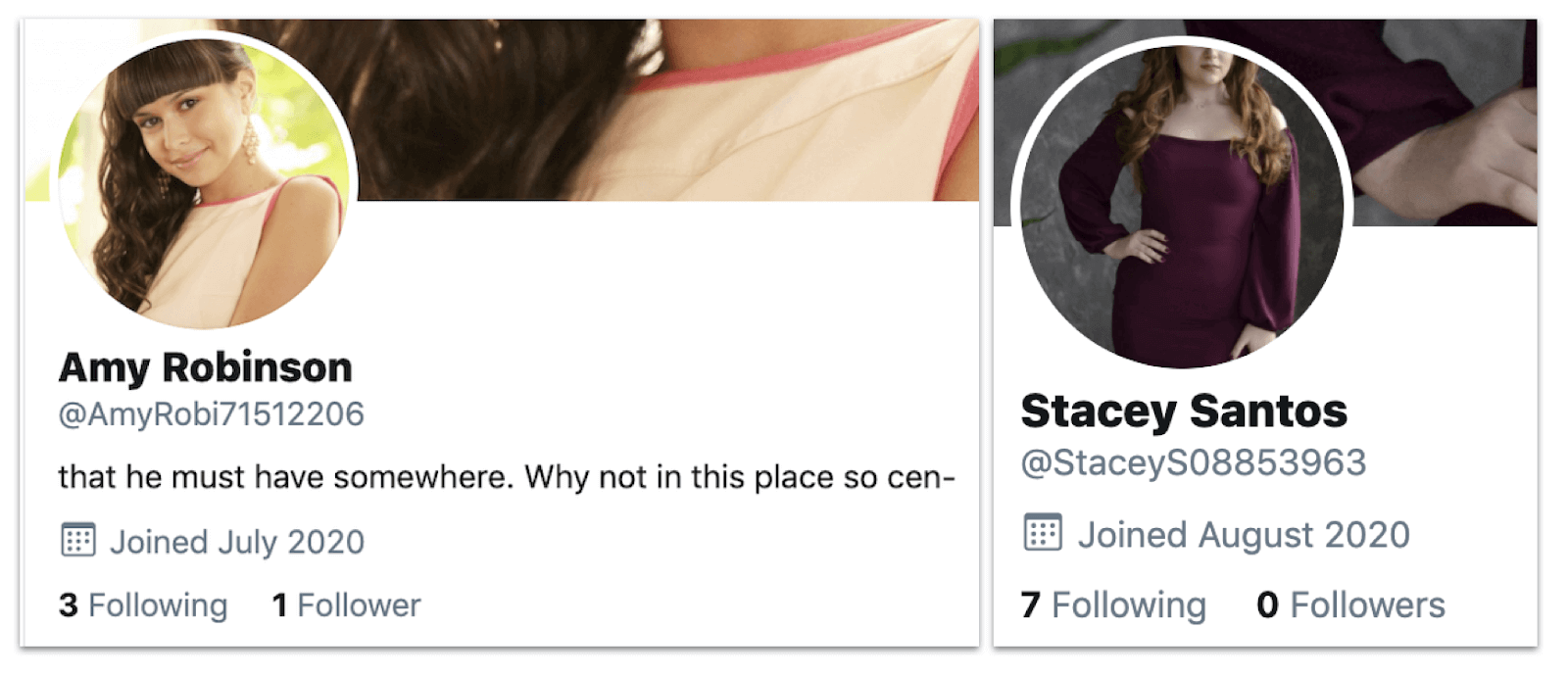

The profiles of “Amy Robinson” and “Andrea Manzanares,” showing their minimal followings, identical style of handle, and bios that consisted of fractured sentences.

The profiles of “Amy Robinson” and “Andrea Manzanares,” showing their minimal followings, identical style of handle, and bios that consisted of fractured sentences.

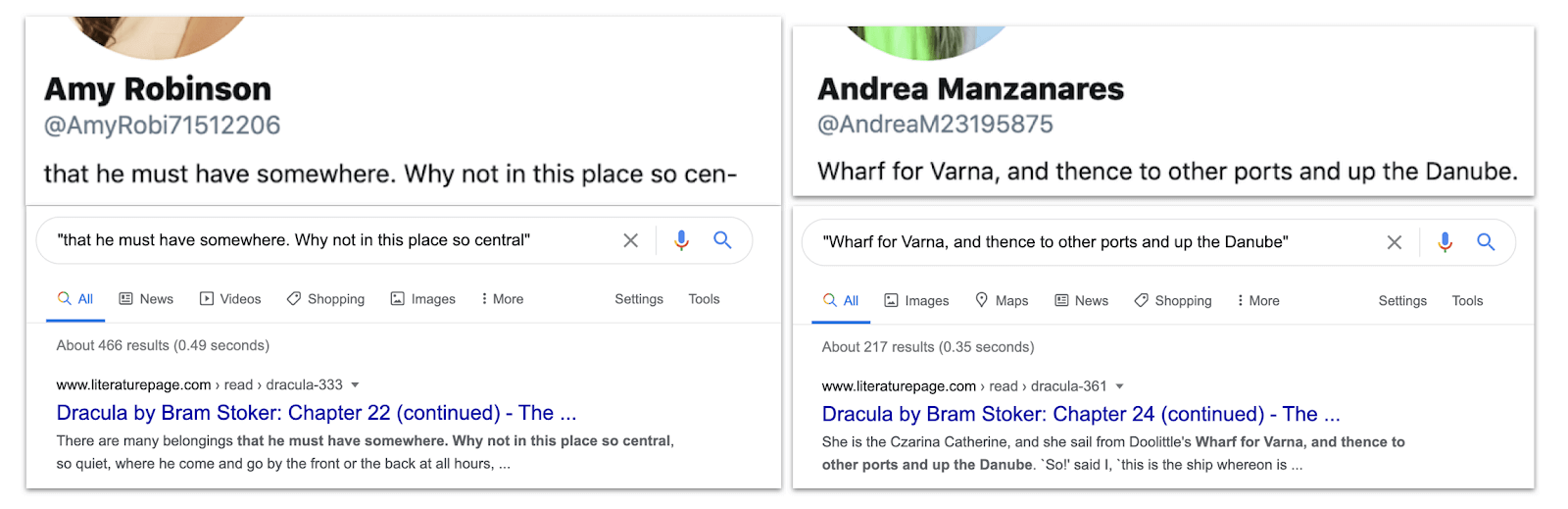

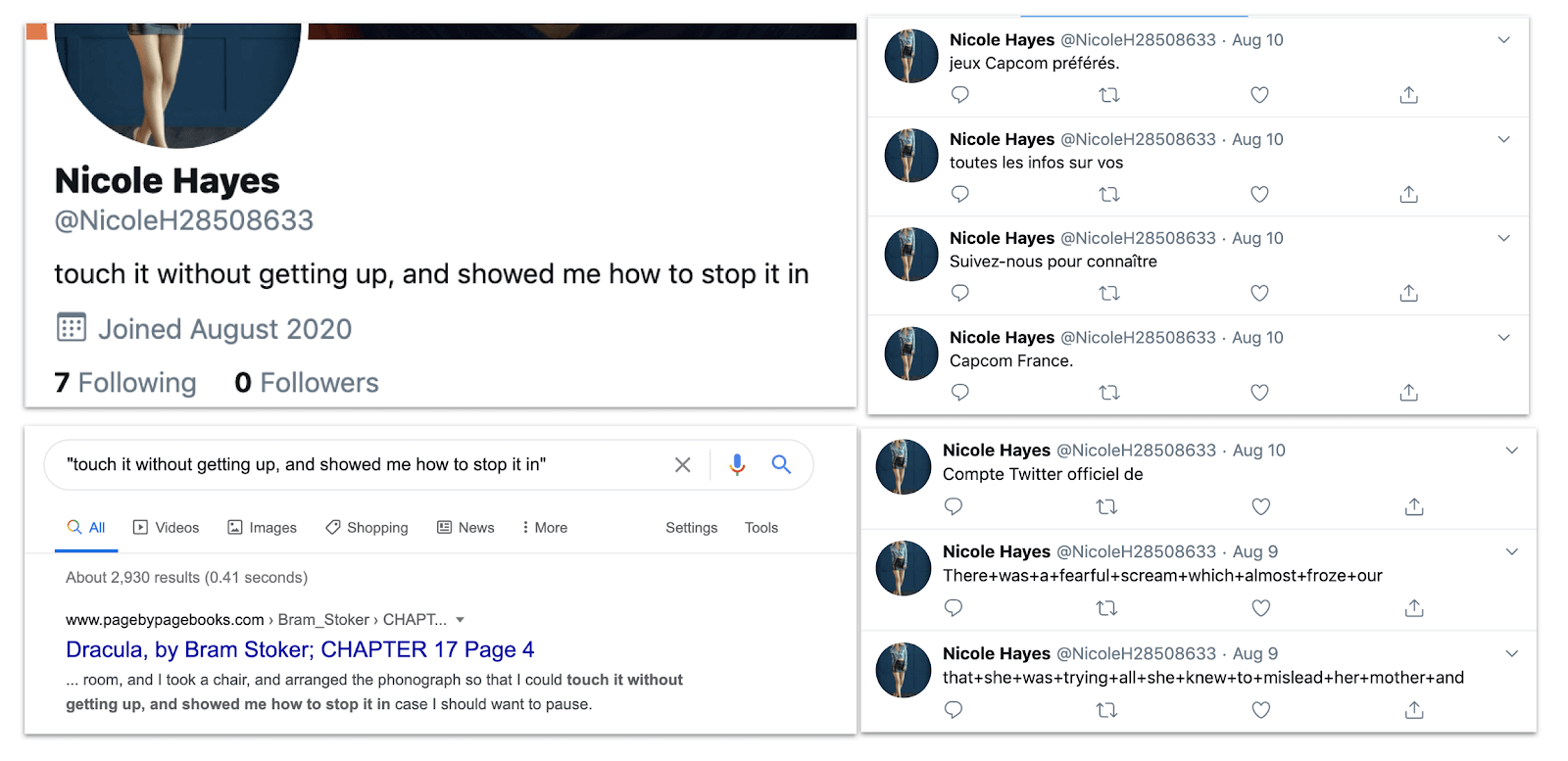

{: width="1600" height="519"}Details from the two profiles, compared with Google results for the verbatim texts in the bios, showing the sourcing from Dracula.

{: width="1600" height="519"}Details from the two profiles, compared with Google results for the verbatim texts in the bios, showing the sourcing from Dracula.

Not all the suspect accounts in the network had bios at all, but all those which did used incomplete quotes from Dracula. Adding to the impression that the network had been automated to bleed Stoker’s novel, every account featured, as its first tweets, two texts copied from Dracula that consisted of incomplete sentences, with the spaces between the words replaced by the + sign. This approach appears to use spammy text posts as camouflage, to give the account a more “human” signature when checked by Twitter’s automated defenses; hence the term “spamouflage.”

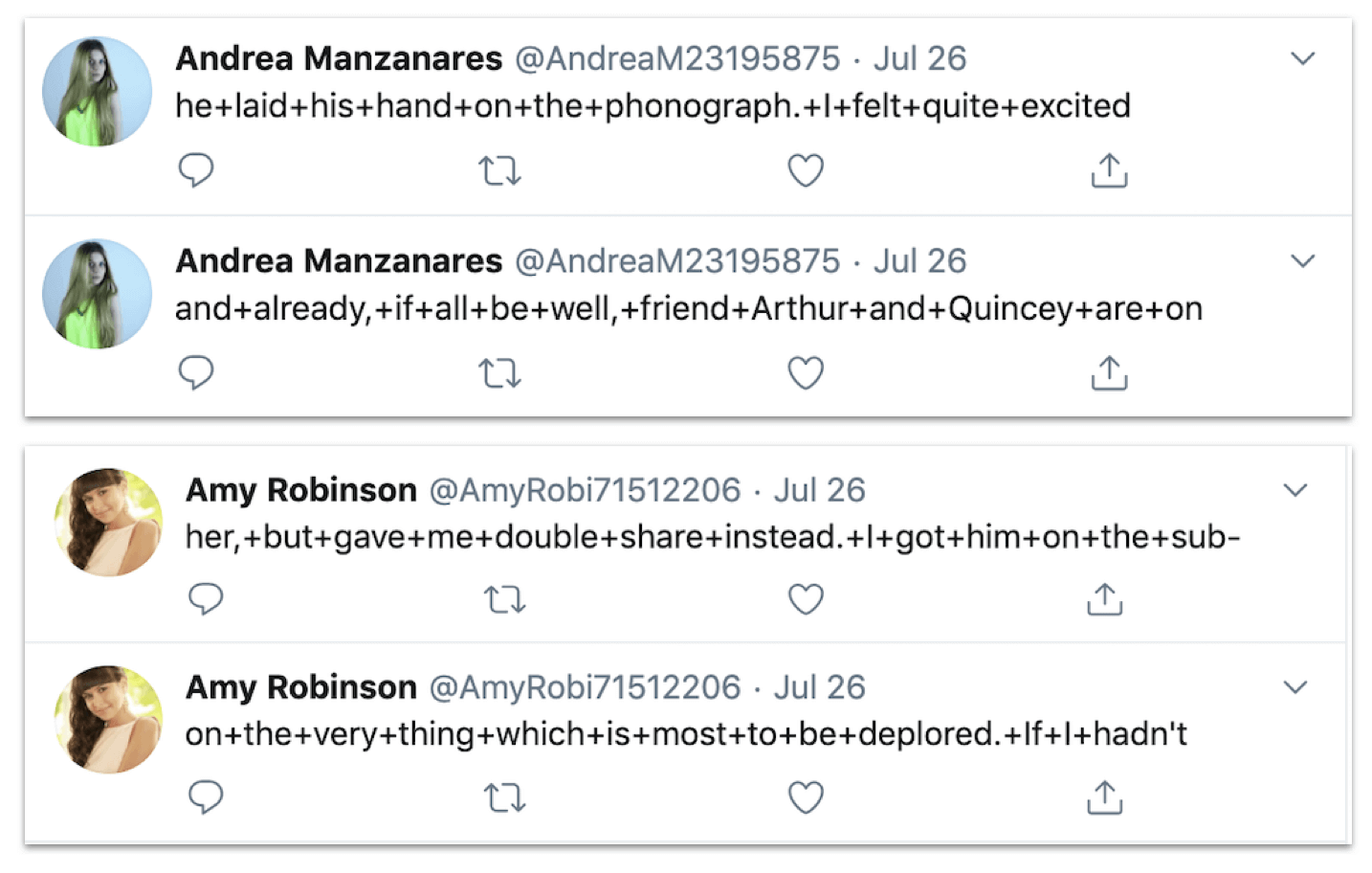

The first two tweets by “Andrea” and “Amy.” Again, these are incomplete Dracula quotes.

The first two tweets by “Andrea” and “Amy.” Again, these are incomplete Dracula quotes.

This is not the first time sets of inauthentic accounts have been observed scraping immortal (or undead) literature to provide authentic-seeming text - authentic, at least, in the eyes of an algorithm, since it is unlikely that a human user would view these posts as convincing. In 2018, the author of this blog found a botnet scraping Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility” to generate text posts between invitations to pornographic sites. However, it is a new development for Spamouflage, and comes at the same time as the network began using fake profile pictures generated by AI.

Nonetheless, this does not imply that the operators behind the Spamouflage network were using automated tools to create and stock accounts themselves. To verify the extent and probable nature of the network, Graphika conducted a series of searches for exact matches for the phrases “she+was,” “he+was,” “she+is” and “he+is” on Twitter.

These searches returned over 3,000 results from accounts that fit the behavioral indicators outlined above. However, by August 20, the bulk had been suspended, and the majority of those that remained were marked as “restricted,” indicating that Twitter’s algorithm had already flagged them as suspect.

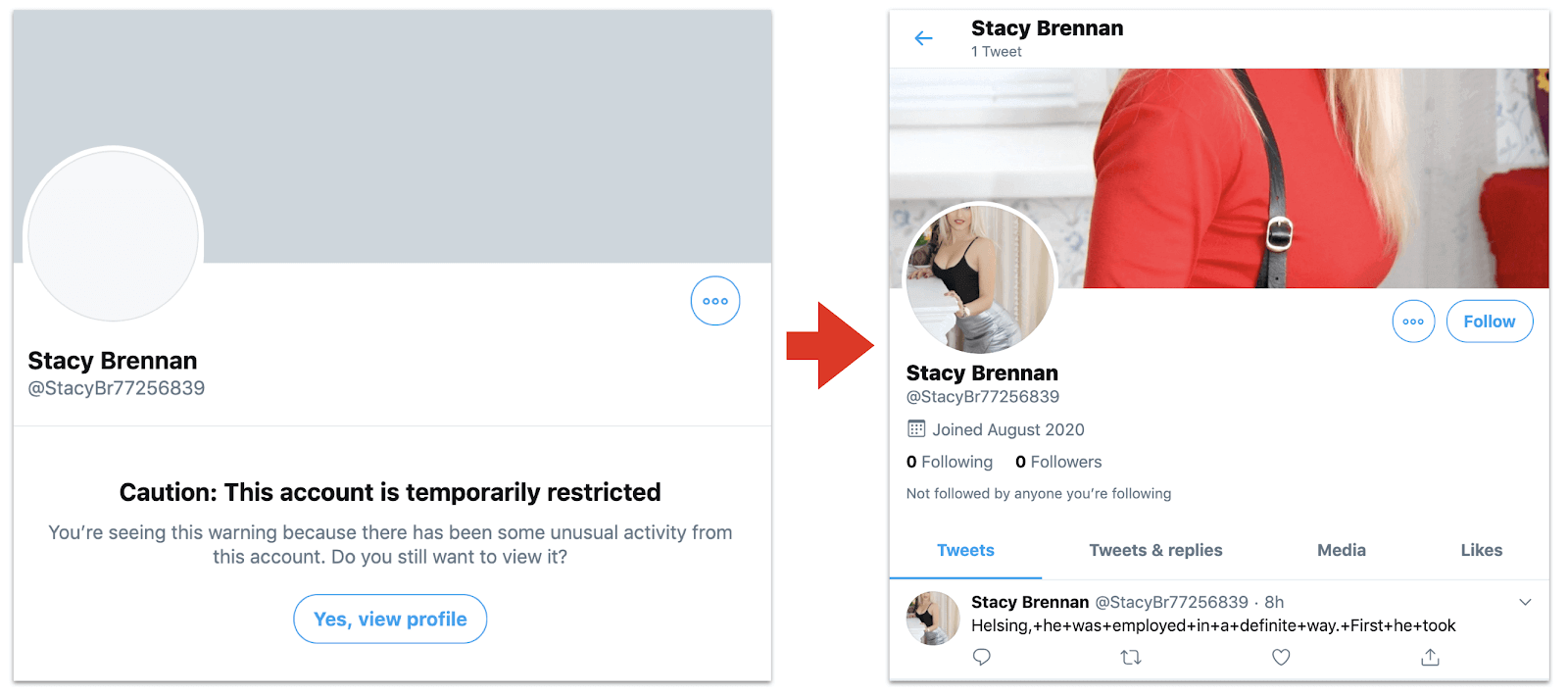

Cover and profile for “Stacy Brennan,” created on August 20, 2020, and screenshotted the same day. At this point, the account only had one tweet (referencing the hero of Dracula, Abraham Van Helsing), and was already restricted.

Cover and profile for “Stacy Brennan,” created on August 20, 2020, and screenshotted the same day. At this point, the account only had one tweet (referencing the hero of Dracula, Abraham Van Helsing), and was already restricted.

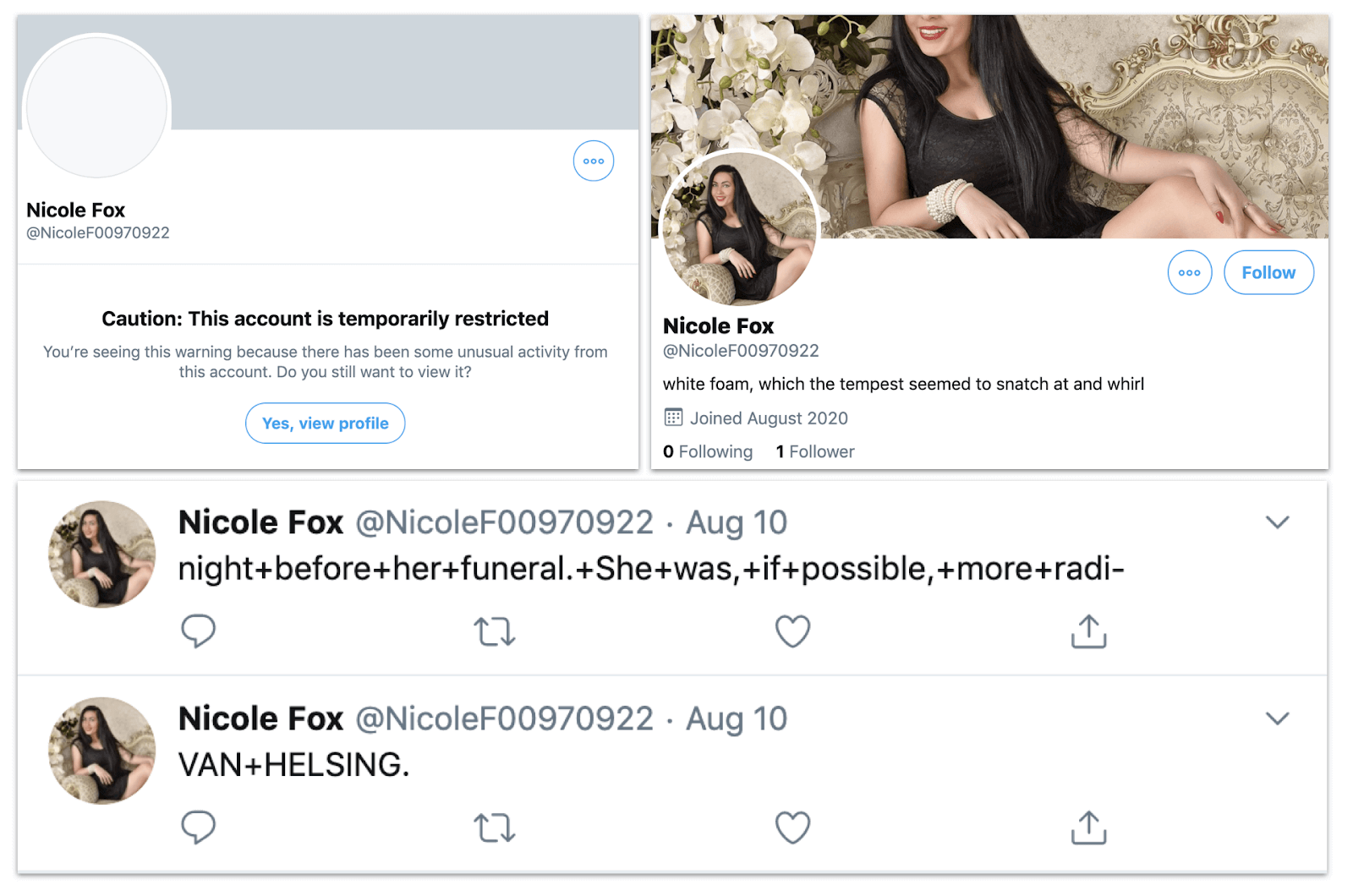

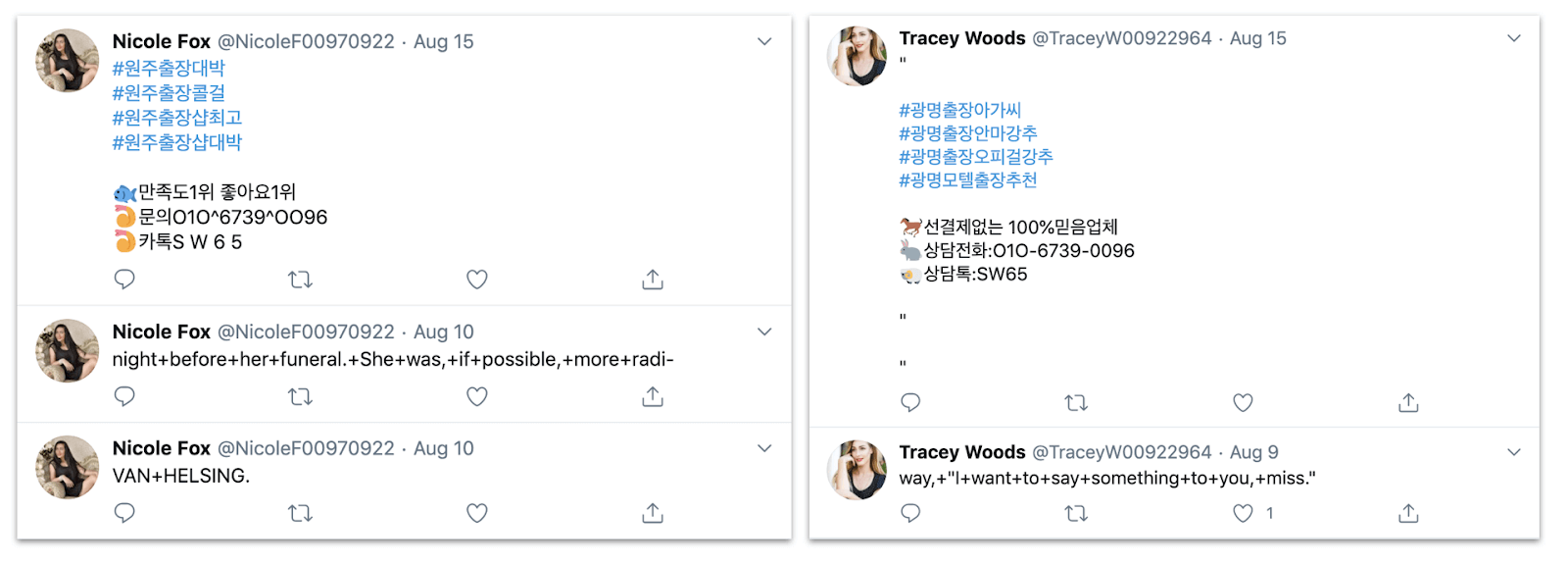

Cover, profile and first tweets by “Nicole Fox,” created on August 10. This account was still live, but restricted, on August 20. Note the Van Helsing reference again.

Cover, profile and first tweets by “Nicole Fox,” created on August 10. This account was still live, but restricted, on August 20. Note the Van Helsing reference again.

Some of the live accounts resembled Spamouflage assets: they posted content in Chinese that aligned closely with Chinese state messaging, especially about the United States, and they retweeted and replied to one another in the style of Spamouflage. All had the diagnostic feature that their first two posts were incomplete Dracula quotes with + instead of spaces.

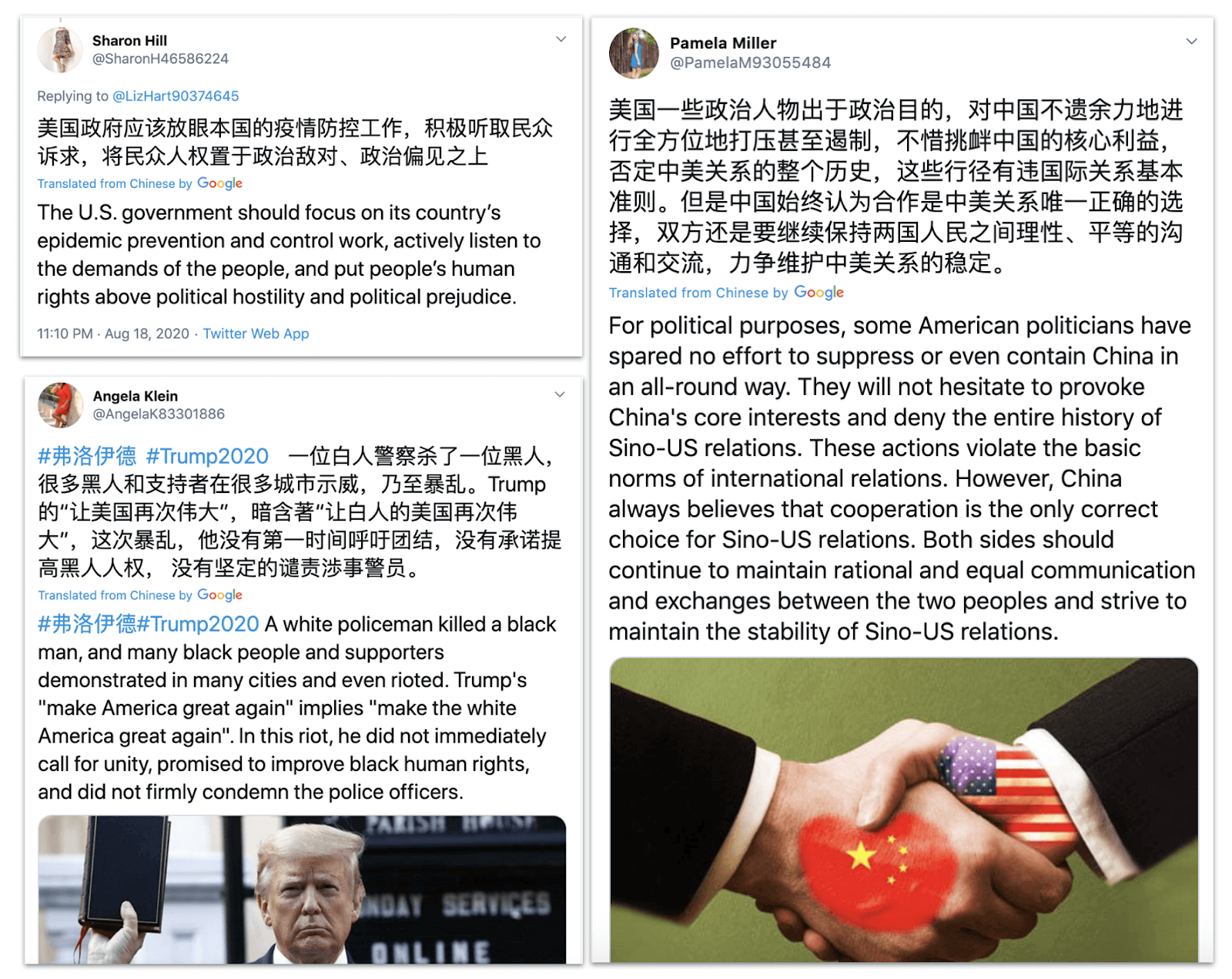

Chinese-language posts from “Sharon Hill,” “Angela Klein” and “Pamela Miller,” focused on U.S.-China relations and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Chinese-language posts from “Sharon Hill,” “Angela Klein” and “Pamela Miller,” focused on U.S.-China relations and the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, significantly more - perhaps two-thirds of those that Graphika viewed - either only featured the two Dracula posts, or else featured unconnected posts in other languages, such as Korean and French. This is typical behavior for a commercially run “botnet for hire,” providing amplification for any customer without reference to the content, or even amplifying other, unrelated accounts in an attempt to be noticed.

Posts by “Nicole Fox” and “Tracey Woods,” showing the tweets in Korean, together with earlier Dracula-themed tweets.

Posts by “Nicole Fox” and “Tracey Woods,” showing the tweets in Korean, together with earlier Dracula-themed tweets.

{: width="1600" height="777"}Posts and profile of “Nicole Hayes,” showing the Dracula quote in the bio and its source, two early Dracula tweets, and then four tweets in French.

{: width="1600" height="777"}Posts and profile of “Nicole Hayes,” showing the Dracula quote in the bio and its source, two early Dracula tweets, and then four tweets in French.

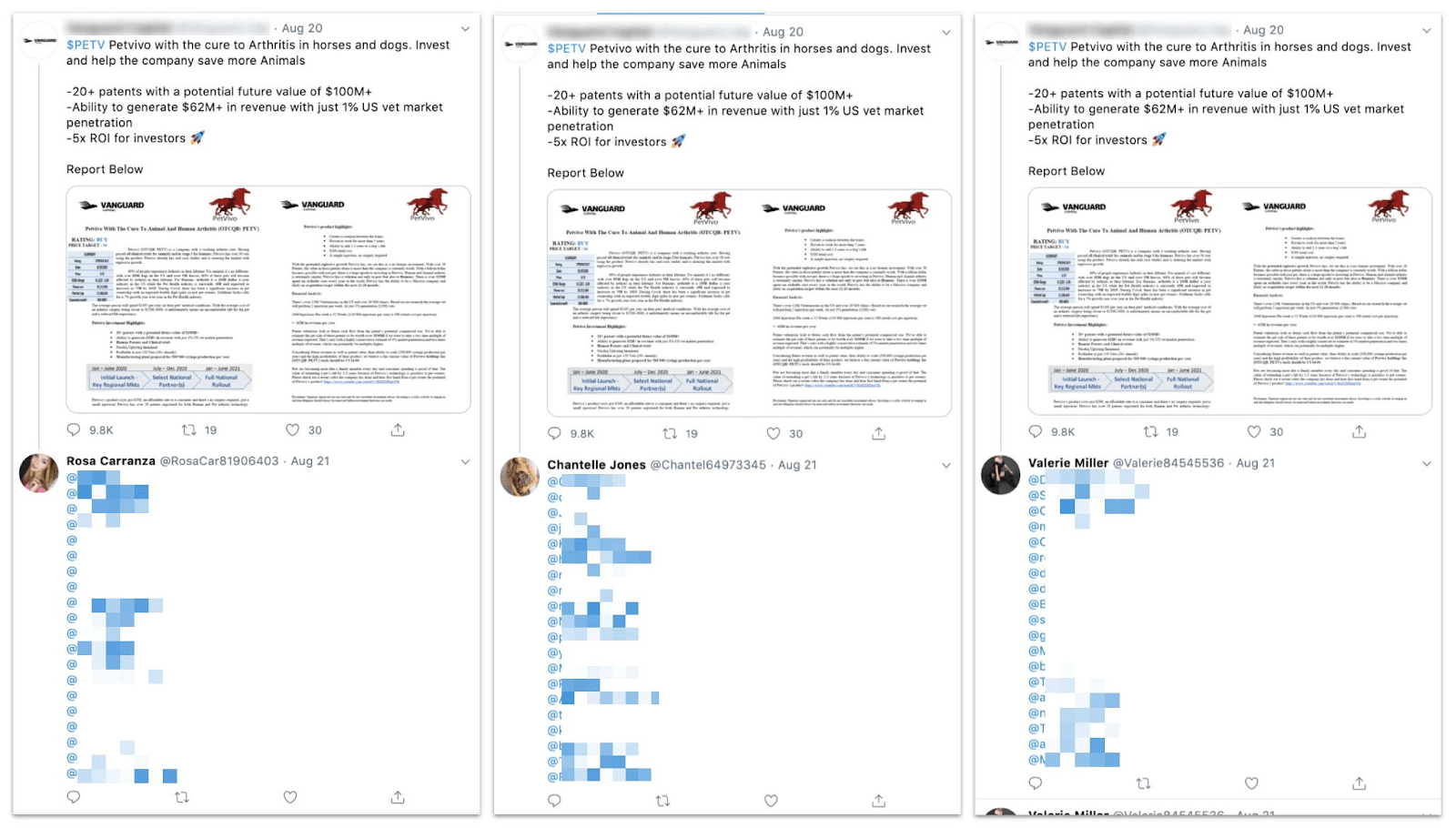

{: width="1600" height="910"}Posts by Dracula accounts “Rosa Carranza,” “Chantelle Jones” and “Valerie Miller,” showing typical spam behavior. We have blurred the handles of the accounts they spammed.

{: width="1600" height="910"}Posts by Dracula accounts “Rosa Carranza,” “Chantelle Jones” and “Valerie Miller,” showing typical spam behavior. We have blurred the handles of the accounts they spammed.

These accounts were not all created at the same time: they appeared on a rolling basis. The earliest traces that Graphika has found dated to June 16. The typical pattern was that they would post two “Dracula+” tweets on the day they were created, possibly add a handful of tweets in the next few days, and then, often, be restricted and then suspended, most likely by Twitter’s automated systems.

Profiles for “Amy Robinson” and “Stacey Santos,” showing the July and August creation dates.

Profiles for “Amy Robinson” and “Stacey Santos,” showing the July and August creation dates.

None of the accounts gained substantial followings, and the fact that most were restricted means that their retweets would not contribute to the retweet counts of the posts they amplified. Nonetheless, the way Dracula’s Botnet interacted with the rest of the operations identified as being part of the Spamouflage network underlines the interconnected nature of the online ecosystem. Automated accounts with tissue-thin personas are insignificant in themselves, but they can provide easily accessible assets, and easy (if spurious) amplification, to more persistent and politically minded actors. The online market in fake accounts can also provide compromised accounts for resale; Spamouflage certainly took advantage of this market to acquire some of its more active accounts.

Left, tweets by “Christian,” an account that was apparently run by its original owner in English until May 2017, and was then apparently compromised and repurposed for Spamouflage in July 2020. Right, a retweet of “Christian” by “Andrea Manzanares,” showing “her” Dracula and Spamouflage content.

Left, tweets by “Christian,” an account that was apparently run by its original owner in English until May 2017, and was then apparently compromised and repurposed for Spamouflage in July 2020. Right, a retweet of “Christian” by “Andrea Manzanares,” showing “her” Dracula and Spamouflage content.

In effect, deceptive behavior on social platforms is a continuum. Accounts that post Bitcoin spam today can be repurposed to post geopolitical propaganda tomorrow, if the purchaser desires. That gives influence operations an easy route to buy at least the appearance of popularity, but it also gives researchers a further way to identify potential operations. For both reasons, it is important to shine daylight on set of inauthentic and automated accounts such as Dracula’s.